Causal manipulation of early noise biases numerosity judgements towards adaptive priors

“Can you do Addition?” the White Queen asked. “What’s one and one and one and one and one and one and one and one and one and one?” “I don’t know,” said Alice. “I lost count.” “She can’t do Addition,” the Red Queen interrupted. by Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking Glass

Choices exhibit some element of randomness. This result is robust across multiple domains in decision-making and perception (Smith & Krajbich, 2018; Prat-Carrabin & Woodford, 2022). Some ways to model noisy decisions include using a softmax operator (Glascher, Daw, Dayan, & O’Doherty, 2010), modeling random utility (), or adding noise to a decision process (Forstmann, Ratcliff, & Wagenmakers, 2016). All of these approaches remain agnostic to the source of the noise. While noise may be introduced late into the decision process at the time of decision-making, it may also arrive early in the process at the time of stimulus encoding. For example, in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass, the White Queen asks Alice what is the sum of “one and one and…”. Confusing presentation and limited time for interpretation led Alice to be uncertain about her estimate of the sum, so much so that she was unwilling to provide an answer. However, if Alice was asked if the sum was more than one or two, it’s not hard to imagine she’d be able to answer “yes” with relative certainty. Similarly, if Alice was given significantly more time to encode the stimulus, one might imagine she’d be able to give a precise estimate of the sum. This example highlights two aspects of numerosity judgements that we will utilize in our task: (1) numerosity judgements are an inference problem, and (2) the precision of the signal, proxied here by duration of stimulus presentation, can have a meaningful impact on noise, bias, and confidence in an estimate.

Early noise has been modeled in visual perception using Bayesian encoding-decoding models (Wei & Stocker, 2012). More recently, the prior at the encoding stage has been modeled as something we’ll call a naturalistic prior". These naturalistic priors arise from frequent interactions with our local environment and bias decisions towards common representations in nature (Girshick et al., 2011).

Recently, this concept of naturalistic priors has infiltrated numerosity perception. The argument is that how often a numerosity is encountered and represented in nature follows a power law, P(x) is proportional to $1/x^2$ (Cheyette & Piantadosi, 2020). The naturalistic prior conflicts with competing models with priors that are capable of adapting to the context (Prat-Carrabin & Woodford, 2022). Note, in fact, that the naturalistic prior model is a special case of the adaptive prior model in which the prior adapts to natural statistics, then ceases to adapt further.

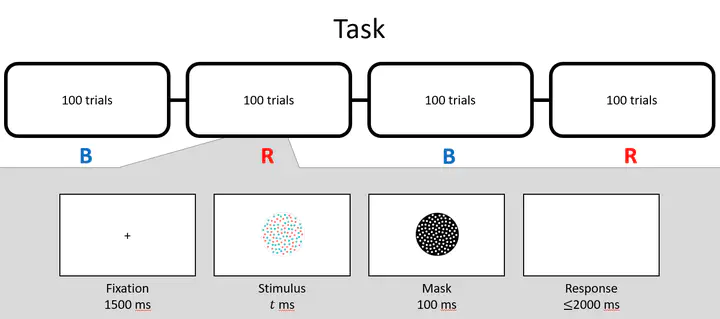

In many contexts, these two models would be indistinguishable since they yield identical predictions. However, when priors are biased away from uniform and stimulus duration is carefully controlled, we start to see differences in predicted choice variance between the two models. In this paper, we aim to utilize these differences in predictions to test the two competing models of numerosity judgements.